Priesthood and Apocalypse

A parting message from Pope Francis

Pope Francis’ final week of mortal life coincided with Holy Week, and ended the day after Easter Sunday. Although he was unable to take part in any of the solemn liturgies of those days due to his illness, he had already written the homilies for each celebration, along with the meditations for the Stations of the Cross at the Colosseum on Good Friday (follow links for the full texts). He was surely aware that this could be his last Holy Week on earth, and composed these texts as a sort of spiritual testament. This is especially clear in the Good Friday meditations, which conclude with a summary of his three encyclicals.

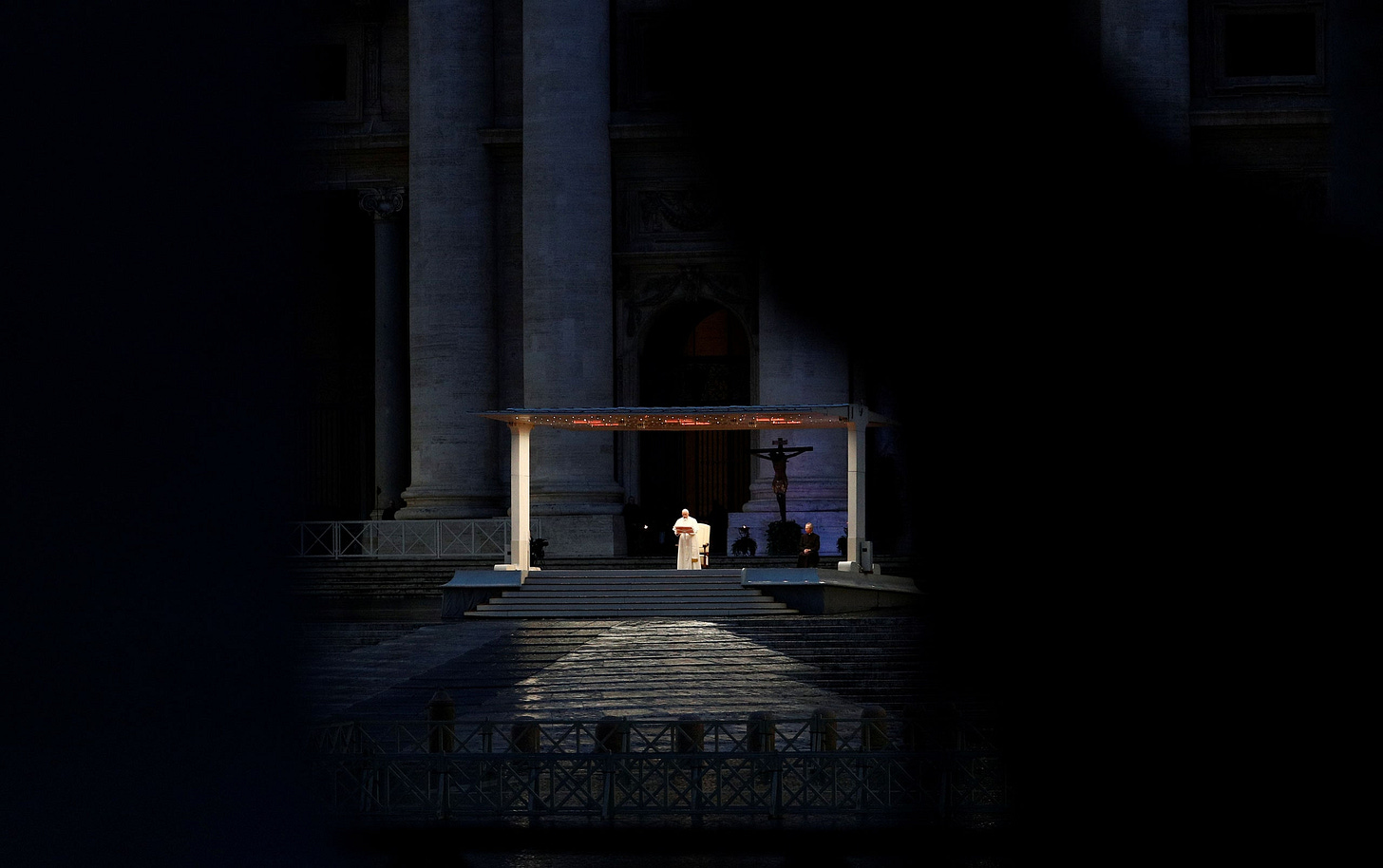

One central element of Francis’ whole magisterium (and of Pope Benedict’s as well), present throughout these final texts, is the Christian theology of history. Francis was sensitive to the “change of epoch” that began in earnest during his pontificate, as the Pax Americana began to unravel. He announced an extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy on the eve of the epoch-marking events of Trump I and Brexit, and provided a symbolic interpretation of the COVID crisis with his vigil of prayer before an empty, rainy St. Peter’s Square, the miraculous crucifix of the 1522 Great Plague of Rome in the background.

Of his final Holy Week texts, the Chrism Mass homily from Holy Thursday contains a particularly expressive summary of the key elements of the Christian view of history, just as they are presented in the classic icon at the top of this page. The Biblical background of that icon pervades the Liturgy of the Word of the Chrism Mass, and Francis took advantage of this to comment on these themes and connect them to the Catholic understanding of priesthood (the Chrism Mass is where the bishop consecrates the holy oil by which the priesthood of Jesus — “Christ” means “anointed one” — is communicated to Christians).

The Old Testament passage at the root of this vision is a line from the Prophet Isaiah, describing the enigma of history, which remains unintelligible even to the recipients of Isaiah’s divinely inspired prophecy:

For you the vision of all this has become like the words of a sealed scroll. When it is handed to one who can read, with the request, “Read this,” the reply is, “I cannot, because it is sealed.” When the scroll is handed to one who cannot read, with the request, “Read this,” the reply is, “I cannot read.” (Is 29:11-12)

This passage is not directly cited in the Chrism Mass or in Pope Francis’ homily, but it is implicitly referenced and developed by Saint Luke and Saint John in the texts of this liturgy. Luke describes how Jesus is “handed” the scroll of Isaiah. For Jesus, it is not “sealed”: he is able to “open” it, and make its content accessible.

He came to Nazareth, where he had grown up, and went according to his custom into the synagogue on the sabbath day. He stood up to read and was handed a scroll of the prophet Isaiah. He unrolled the scroll and found the passage where it was written:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring glad tidings to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to proclaim a year acceptable to the Lord.”

Rolling up the scroll, he handed it back to the attendant and sat down, and the eyes of all in the synagogue looked intently at him. He said to them, “Today this scripture passage is fulfilled in your hearing.” (Lk 4:16-21)

Isaiah also provides the explicit backdrop for John’s vision in the Book of Revelation, which refers directly to the problem of the “seals” on the scroll, which prevented anyone from opening it and making sense of the story of the world. After John laments this situation, the Lamb of God appears (as in the icon above) and is declared worthy to finally break open the seals:

Worthy are you to receive the scroll

and to break open its seals,

for you were slain and with your blood you purchased for God

those from every tribe and tongue, people and nation.

You made them a kingdom and priests for our God,

and they will reign on earth. (Rev 5:9-10)

Both Luke and John teach that the event of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection provides the essential key for unlocking the meaning of history, opening the seven seals that had previously hidden it from mortal eyes.

The Pope begins his homily by summarizing this teaching, starting from another passage of Revelation, from the First Reading of the Mass, and connecting John’s vision to Luke’s account:

“The Alpha and the Omega, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty” (Rev 1:8), is Jesus himself. That same Jesus whom Luke presents to us in the synagogue of Nazareth, among those who have known him since he was a child, and are now amazed at him. Revelation — “apocalypse” — takes place within the limits of time and space: it has flesh as the hinge (caro cardo) that sustains our hope. Jesus’ flesh and our own flesh. The final book of the Bible speaks of this hope. It does so in an extraordinary way, by dispelling all apocalyptic fears in the light of crucified love. In Jesus, the book of history is opened, and can be read.

Francis calls special attention to the role of the Holy Spirit in Luke’s version. Using the words of Isaiah, Luke explains how Jesus is empowered to fulfill the promises of God — and thus unlock the riddle of history — through the “anointing” of the Spirit:

The eyes of all are now fixed on Jesus. He has just proclaimed a jubilee. He did so, not as someone speaking about others but about himself. He said: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me”, as someone who knows the Spirit of which he speaks. Indeed, he adds: “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” This is divine: the word becomes reality. The facts now speak; the words are fulfilled. Something new and powerful is happening. “See, I am making all things new.” There is no grace, there is no Messiah, if the promises remain promises, if they do not become reality here below. Everything is now changed.

This same anointing is shared by all Christians, symbolized by the chrism that is consecrated in this Mass. Francis addresses himself to those who have received the particular mode of priesthood reserved to successors of the Apostles and their immediate collaborators, called to make Jesus’ proclamation palpable to the rest of the faithful:

We now invoke this same Spirit upon our priesthood. We have received that Spirit, the Spirit of Jesus, and he continues to be the silent protagonist of our service. The people feel his breath when our words become a reality in our lives. The poor before all others, children, adolescents, women, but also any who have been hurt in their experience of the Church: all these have a “feel” for the presence of the Holy Spirit; they can distinguish him from worldly spirits, they recognize him in the convergence of what we say and what we do. We can become a prophecy fulfilled, and this is something beautiful! The sacred chrism that we consecrate today seals this mystery of transformation at work in the different stages of Christian life. Take care, then, never to grow discouraged, for it is all God’s work. So believe! Believe that God did not make a mistake with me! God never makes mistakes. Let us always remember the words spoken at our ordination: “May God who has begun the good work in you bring it to fulfilment.” He does.

The Pope goes on to describe the essence of priestly ministry as the continuation of Jesus’ proclamation in Nazareth — bringing Isaiah’s prophecy to fulfillment within history, discretely but truly, by the power of the Holy Spirit:

It is God’s work, not ours: to bring good news to the poor, freedom to prisoners, sight to the blind and freedom to the oppressed. If Jesus once found this passage in the scroll, today he continues to read it in the life story of each one of us. First and foremost, because until our last day, he continues to tell us good news, to free us from prisons, to open our eyes and to lift the burdens from our shoulders. Yet also, because by calling us to share in his mission and sacramentally giving us a share in his life, he sets others free through us, often without our even knowing it. Our priesthood becomes a jubilee ministry, like his, accomplished without fanfare but through a devotion that is unobtrusive, yet radical and gratuitous. It is that of the Kingdom of God, the one recounted in the parables, effective and discreet like yeast, silent like seed. How often have the little ones recognized it in us? And are we able to say thank you?

He concludes the homily by turning to the rest of the faithful, reiterating the message of hope, which is the theme of this Jubilee Year:

Dear members of the faithful, people of hope, pray today for the joy of priests. May all of you experience the liberation promised by the Scriptures and nourished by the sacraments. Many fears can dwell within us and terrible injustices surround us, but a new world has already been born. God so loved the world that he gave us his Son, Jesus. He pours balm upon our wounds and wipes away our tears. “Look! He is coming with the clouds” (Rev 1:7). His is the Kingdom and the glory forever and ever. Amen.