As “brother, friend,... father,” Escrivá has led the reader through the traditional stages of Christian life, from praxis through theoria physike to theologia. It is now time to discover the maternal role of the Church, as imaged by Mary the mother of Jesus, which has been silently sustaining this whole process from the beginning. It is here that the insights of Marx and other contemporary social theorists become most relevant, as Escrivá describes the supernatural social matrix from which Christ can be born anew. And it is these “other Christs,” these almas de criterio, who change the world by establishing the Kingdom of God.

The “matter” of any social entity is the set of relations among the members and of the members to the whole. Marx saw how the character of these relations shapes the ground of human consciousness, the fundamental framework by which each individual perceives and reacts to things and events. The relations, in turn, are generated and sustained by social practices, shared activities in pursuit of a common end. These practices give a certain stable form to the society, fostering certain kinds of relations and suppressing others. To understand any society, including the supernatural one, we need to examine both the relations that constitute it and the practices that explain these.1

The fundamental relation that constitutes the Church is radical, trusting, obedient receptivity to the action of God. This is why Mary is the icon of the Church. Her divine maternity is made possible by her free response of total availability to the plan of God for her. This response is so important for the whole Christian story that it has its own shorthand name: fiat — the verb of her reply to the angel in the official Latin translation of the Gospel of Luke. All the other relations in the Church and all the practices that sustain them support or flow from the Marian fiat. This openness to God is inseparable from a maternal embrace of all his creatures, accepting and welcoming everyone unconditionally. The fiat of Mary thus also makes her the new Eve, the “mother of all the living”; and in the Church, it is the foundation of “catholicity,” the Greek term for universality, embracing all people of all times and cultures.

After an introductory chapter (ch. 20) refreshing the overall context of world change, Escrivá systematically lays out this whole picture. He starts with a chapter on Mary herself, focused on her fiat (ch. 21), and then sketches the corresponding structure of relations and practices in a chapter on the Church (ch. 22). Then comes a pair of chapters dedicated to the principal practice (ch. 23) and the principal mode of relation (ch. 24), followed by a brief orientation on how to approach to the overwhelming diversity of secondary practices that have been built up over the past two millennia in the Church’s tradition (ch. 25). The rest of the section (ch. 26-35) deals with the stable interior dispositions entailed by the fiat, which are presupposed by – and thus reinforced by – the other practices and relations. By the end of the section, the reader is gratefully aware of the divinely inspired social fabric that has sustained his journey so far, and conscious of the ways he needs to continue maturing in order to fully resonate with its intrinsic logic.

Since this essay has already been delayed too long, I will not attempt to give a full explanation of this interpretation here, but limit myself to commenting on a few illustrative passages to give at least a taste of this section.

Resources for world change (chapter 20)

First of all, the introductory chapter picks up on the introduction to the first section, channeling the reader’s response to that audacious invitation (“...and set aflame all the ways of the earth with the fire of Christ that you bear in your heart”) in a way that faintly echoes Mary’s first response to the angel (“how can this be?”):

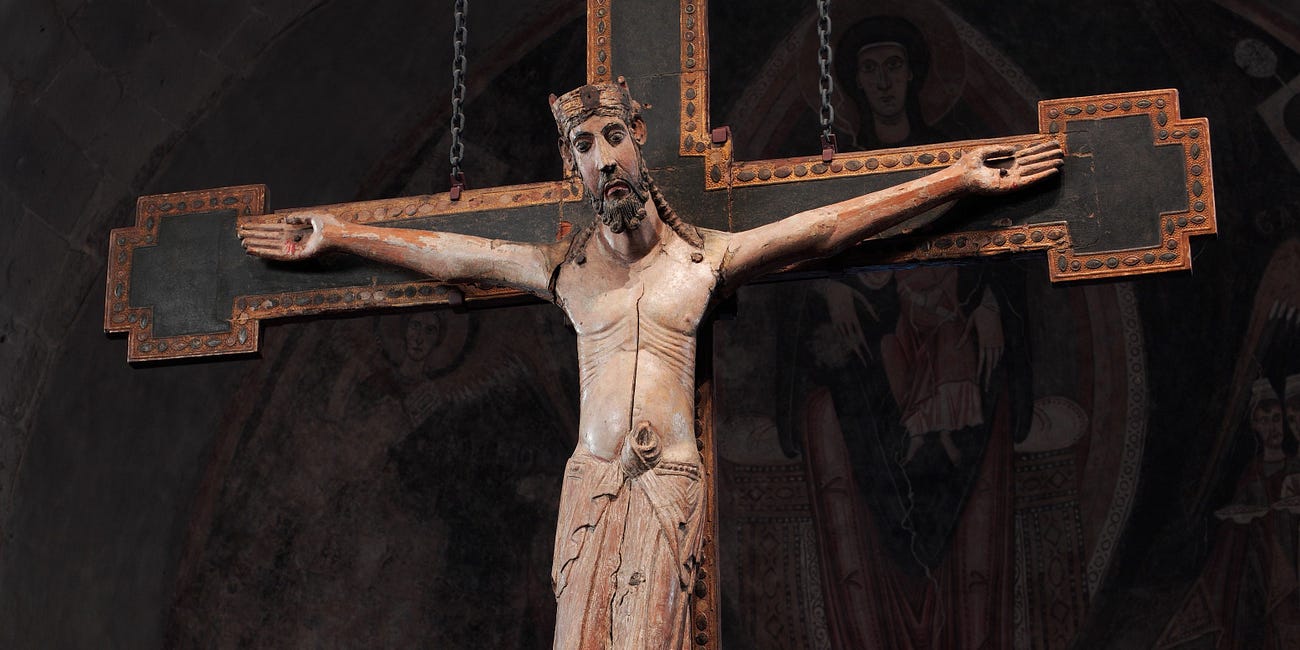

But... with what resources? —The same ones Peter and Paul had, and Dominic and Francis, and Ignatius and Francis Xavier: the Crucifix and the Gospel... —Perhaps these seem small to you?2

The main point of this chapter is to highlight the absolute priority of the divine initiative in positive world change, to prepare for the overall focus of this section on the fiat. It’s interesting to look more closely at the six individuals chosen as examples. The implication of the passage is that each of these actually lived up to the initial invitation, changing the world in a lasting way with the fire of Christ. And each of them did this by establishing or helping to lead a new social entity, composed of distinctive practices and the consequent relations, all characterized by radical receptivity to the Spirit of God: the Church, the mendicant orders, the Jesuits. These names thus provide a concrete introduction to the social focus of this chapter.

Mary (chapter 21)

The chapter on Mary begins with a series of points on the power of love for her:

Love for our Mother will be the breath that enkindles in living flame the embers of virtue hidden in the ashes of your lukewarmness.

Love Our Lady. And She will obtain for you abundant grace to conquer in this daily struggle. – And the evil one will gain nothing from those perverse things that rise and boil within you, seeking to erase with their sweet-smelling rottenness the grand ideals, the sublime commands that Christ himself has placed in your heart. – “Serviam!”

Be Mary’s and you will be ours.3

The first point highlights the “descending” side of Mary’s fiat, how her openness to God makes her the welcoming mother of all men and women. This characteristic makes it easy to run to her with confidence, even from a condition of guilt and unworthiness, even when the “fire of Christ” is almost extinguished by the “lukewarmness” of a selfish heart. Anyone can turn to her with love and trust – and this love immediately begins to fan those embers back into flame, bringing the comatose soul back to life.

The second point develops this further, explaining how love for Mary leads precisely to participation in her fiat, here expressed with another Latin term “Serviam!” — “I will serve.” The third point draws out the clear conclusion: this “belonging” to Mary, sharing in her fiat, is the path by which someone comes to enter this supernatural social reality, the “we” of the Church that is built on this fundamental relation.

The Church (chapter 22)

The chapter on the Church begins with a series of points that mirror this initial triad, linking the Church’s maternity to Mary’s. It goes on to trace the main practices and relations of the Church, starting with the essential practices known as the Sacraments:

How good is Christ to have left his Church the Sacraments! – They are the remedy for every need. – Venerate them and be very grateful to the Lord and to his Church.4

The Sacraments (Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Confession, Anointing of the Sick, Marriage, Holy Orders) initially look like any other social practice. What sets them apart is that they involve God himself as the protagonist of the activity. Their whole structure is built on the assumption that it is God who acts, and their power to constitute the Church – by fostering and strengthening the fiat – depends on their being experienced this way (with “veneration”). If this assumption is false, then the whole thing is a fraud, worthy of being unmasked as a tool of violence and manipulation. But if it is true, then there is a place from which the Kingdom of God can be born.

Faith (chapter 26)

This act of faith is the subject of the first chapter in the next part, on the personal virtues bound up with the fiat:

With what accursed lucidity Satan argues against our Catholic Faith! But, let us always tell him, without entering into debate: I am a son of the Church.5

This point immediately links the question of faith back to the relational context – specifically the relation of filiation, being a son or daughter. This relationship takes priority over all others, since it refers to the origin of one’s very being, the precondition for all other activity. Here, Escrivá boldly affirms that the spiritual filiation to the Church takes precedence even over rational argument. The “son of the Church” is aware that his identity and spiritual vitality flow from his Mother. That immediate awareness overrides any merely conceptual chain of argument. What at first may seem like fundamentalist anti-intellectualism is really an entryway into a robust relational epistemology, a promising path for overcoming the antinomies of Enlightenment rationalism.

These are just a few of the possible directions for further reflections on the Church’s maternity in Camino. In the next essay, we will look at the final section — on how the cooperation of Mary and Joseph leads to the incarnation of Christ himself in the soul, and on the world-transforming dynamism that results.

Camino (part 5)

… an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream, and said, Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take thy wife Mary to thyself, for it is by the power of the Holy Spirit that she has conceived this child; and she will bear a son, whom thou shalt call Jesus,

Footnote 4 to Chapter 15, Volume 1 of Capital provides a clear sketch of this point, focusing on the technological practices aimed at providing for the material necessities of life, but in a way that is more generally applicable: “Technology reveals the active relation of man to nature, the direct process of the production of his life, and thereby it also lays bare the process of the production of the social relations of his life, and of the mental conceptions that flow from those relations.”

Camino 470: Pero... ¿y los medios? —Son los mismos de Pedro y de Pablo, de Domingo y Francisco, de Ignacio y Javier: el Crucifijo y el Evangelio... —¿Acaso te parecen pequeños?

Camino 492: El amor a nuestra Madre será soplo que encienda en lumbre viva las brasas de virtudes que están ocultas en el rescoldo de tu tibieza.

493: Ama a la Señora. Y Ella te obtendrá gracia abundante para vencer en esta lucha cotidiana. —Y no servirán de nada al maldito esas cosas perversas, que suben y suben, hirviendo dentro de ti, hasta querer anegar con su podredumbre bienoliente los grandes ideales, los mandatos sublimes que Cristo mismo ha puesto en tu corazón. —"Serviam!"

494: Sé de María y serás nuestro.

Camino 521: ¡Qué bondad la de Cristo al dejar a su Iglesia los Sacramentos! —Son remedio para cada necesidad. —Venéralos y queda, al Señor y a su Iglesia, muy agradecido.

Camino 576: ¡Con qué infame lucidez arguye Satanás contra nuestra Fe Católica! Pero, digámosle siempre, sin entrar en discusiones: yo soy hijo de la Iglesia.