Technology and Responsibility (Part 2 of 4)

Romano Guardini on the challenges and opportunities of our strange age

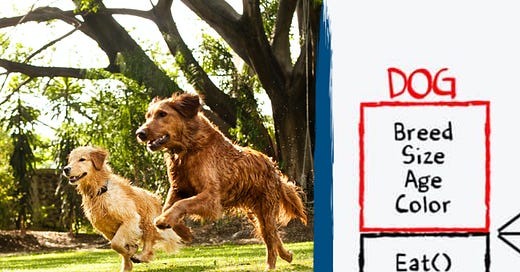

Merriam-Webster’s Learner’s Dictionary defines “technology” as “the use of science in industry, engineering, etc., to invent useful things or to solve problems.” This simple explanation captures the feature of technology that distinguishes it from previous systems of production and use of tools: the application of science. The union of science with practical work is a novelty in human history. It required a new way of knowing, one capable of bridging the methodological gap that previously existed between the sciences and the arts. This transformation in our way of relating to the natural world is what makes possible our unprecedented power over nature, but it also creates new challenges for the exercise of moral responsibility.

As explained in Part 1, Romano Guardini dedicates a significant portion of The End of the Modern World to analyzing the nature of these challenges. He begins by describing the existential context of human work prior to 1900. The word “human” derives from the same root as the Latin word “humus” — the earth, the soil. On this basis, Guardini uses the concept “human” to refer to a mode of personal existence that belongs to the earth, inhabiting the given structures of nature. Even as man modified his surroundings through his work, making and using tools that at times were quite powerful, it remained true that

[w]hat he laid hold of were essentially the things of nature as he could see, hear, and grasp them with his senses. ... his work drew on Nature’s energies, utilized its materials, developed its forms, but left its substance essentially intact. Man ruled Nature by inserting himself into it.1

In other words, the realm of work (Wirkfeld) — the practices, expertise and possibilities of sustained human effort — was contained within the “ordinary world,” the realm of common sense and immediate experience (Erlebnisfeld).2

In this context, the application of science to work is inconceivable. Guardini does not elaborate on this point, but it follows straightforwardly from the nature of science itself. Science deals with universals, formulating general statements that are true always and everywhere. There is a science of trees, describing the basic properties shared by all trees, but there can be no science of this individual black walnut in the corner of the garden. The very existence of this particular tree depends on a host of contingent factors, including the founding of Rome, the defeat of the Turkish fleet at Lepanto, the founding of Opus Dei, etc., etc., down to the whim of a former resident of this house who decided it would be nice to bring some saplings back from America to plant near the pool. But work, in its “human” form, deals with particulars. When I care for this tree, pruning it, watering it, fertilizing it, I enter into a relationship with it. I see the tree as an individual being, rather than simply an instance of the class “tree.” Or to take a more vivid example, from a different kind of work, “He calleth his own sheep by name and leadeth them out” (Jn 10:3).

In the second half of the nineteenth century, all this began to change, as governments and capitalists became aware of the imminent possibility and immense promise of deliberately applying the new form of natural science to industrial production.3 A crucial step in this process was the establishment of uniform standards of measurement, by which particular objects of human effort could be represented as interchangeable instances of a universal type, whose individual characteristics would be indicated by a set of numerical values.4 At first, these models were simply a form of rigorous bookkeeping, giving a more precise account of observations that were still accessible to the unaided human senses. But the mediation of measurement apparatus and mathematical formalism opened new possibilities for human knowledge and action, which were no longer limited to the realm of immediate experience.5 Eventually, this abstract representation of the natural world comes to be seen as the primary, basic reality:

This changes man’s relationship with nature. It loses its immediacy, and is conveyed indirectly, through calculation and apparatus. It loses its concrete visibility, and becomes abstract and formal. It loses its ability to be experienced, and becomes objectified and technical.6

The result of this change is a rupture of the unity between the realm of action (Wirkfeld) and the realm of experience (Erlebnisfeld). Man no longer inhabits the soil, adapting the given structures of nature to his own use while leaving them essentially intact. Instead his work increasingly consists in the manipulation of symbols within abstract frameworks of his own devising, with sensors and machines mediating his contact with the external world. The man who lives this way is no longer human, in the sense described above.7 Guardini takes pains to avoid making a value judgment on this situation, which has consequences both for good and for ill. The inhabitants of industrially developed nations already live a non-human mode of existence, whether they like it or not, and need to learn to deal with this reality.

This is not to say that this non-human mode is permanent. The historical processes that Guardini identified have continued more or less as he predicted over these seventy years that have passed since the publication of his book, completing the transformation to a degree that he himself could never have imagined. But the new form of social organization is rapidly losing its coherence and stability, and it seems increasingly unlikely that it will outlive the 21st century. Many people from a variety of social and intellectual backgrounds already feel the urgency of integrating technology into a renewed human way of life — making it a tool for facilitating relationships with other people and with the the natural world. This is a radical proposal, entailing a substantial demotion of mathematical science from the ultimate arbiter of truth to (more or less) a gardening implement. Articulating such a program requires deep study of the real nature and just status of this kind of knowledge. In future essays, I plan to examine two prime examples of such study: French philosopher Jacques Maritain’s Degrees of Knowledge, and British psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and his Emissary. I also think it’s worth commenting on Kanye West’s intuition about Wakanda as a model for the future of technology — there’s a lot more there than people give him credit for.

But for the current four-part series, the focus is on the present: given that we currently inhabit a non-human society, how do we go about exercising moral responsibility? As I noted in Part 1, the mediation of abstract systems severely inhibits the operation of “common-sense” morality. You can easily steal, or kill, or lie, without realizing what you are doing — and on a much grander scale than even the greatest emperors were capable of in the past. Before exploring this problem (in Part 4), however, we need to look at the second source of difficulty, stemming from the social dimension of technological production.

Was er erfaßte, waren im Wesentlichen die Dinge der Natur, wie er sie mit seinem Sinnen sehen, hören, greifen konnte. ... was er tat, benutzte ihre Energien, verwertete ihre Stoffe, entwickelte ihre Formen, ließ aber ihren Bestand im Wesentlichen unversehrt. Der Mensch beherrschte sie [Natur], indem er sich in sie einfügte. (p. 80-81)

Vielleicht kann man es [der Begriff des “Humanen”] als die Tatsache bestimmen, daß das Wirkfeld dieses Menschen mit seinem Erlebnisfeld zusammenfiel. (p. 80)

See David Noble, America by Design (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977) for an extremely detailed history of this process within the political, educational and industrial institutions of the United States.

See Peter Galison, Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps: Empires of Time (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003) for a compelling narrative of some of the key players who made this happen on the international stage. Note that these comments on the concrete historical implementation of the transformation is beyond the scope of Guardini’s book; he focuses on the general features of the overall process.

Dann wandelt sich das Verhältnis. Das Feld des Erkennens, Wollens und Wirkens des Menschen überschreitet, erst in einzelnen Fällen, darauf immer häufiger, schließlich einfachhin den Bereich seiner unmittelbaren Organisation. (p. 82)

Dadurch verändert sich sein Verhältnis zur Natur. Es verliert die Unmittelbarkeit, wird indirekt, durch Rechnung und Apparat vermittelt. Es verliert die Anschaulichkeit; wird abstrakt und formelhaft. Es verliert die Erlebbarkeit; wird sachhaft und technisch. (p. 82)

Den Menschen, der so lebt, nennen wir den "nicht-humanen" Menschen. Auch dieses Wort drückt kein sittliches Urteil aus, ebensowenig wie das des "humanen." Es meint eine geschichtlich gewordene und sich immer schärfer betonende Struktur -- jene, in welcher das Erlebnisfeld des Menschen von seinem Erkenntis- und Wirkfeld grundsätzlich überschritten wird. (p. 83)

"Science deals with universals, formulating general statements that are true always and everywhere. There is a science of trees, describing the basic properties shared by all trees, but there can be no science of this individual black walnut in the corner of the garden."

This has become something of a crisis in my own life as a practicing scientist. There is something tragic about approaching a thing you love with the tools of generalization and abstraction, only to find yourself embracing a phantom of words or numbers, more distant than ever from the true object of your affection. A distinction between the "no-thing" of generalization and "nothing" of nihilism may ultimately be hard to maintain.

Is there, then, a way to practice science with joy and childlike wonder, somehow bracketing off its dismal abstraction while harnessing its insights unto a richer enjoyment and closer approach of real things?